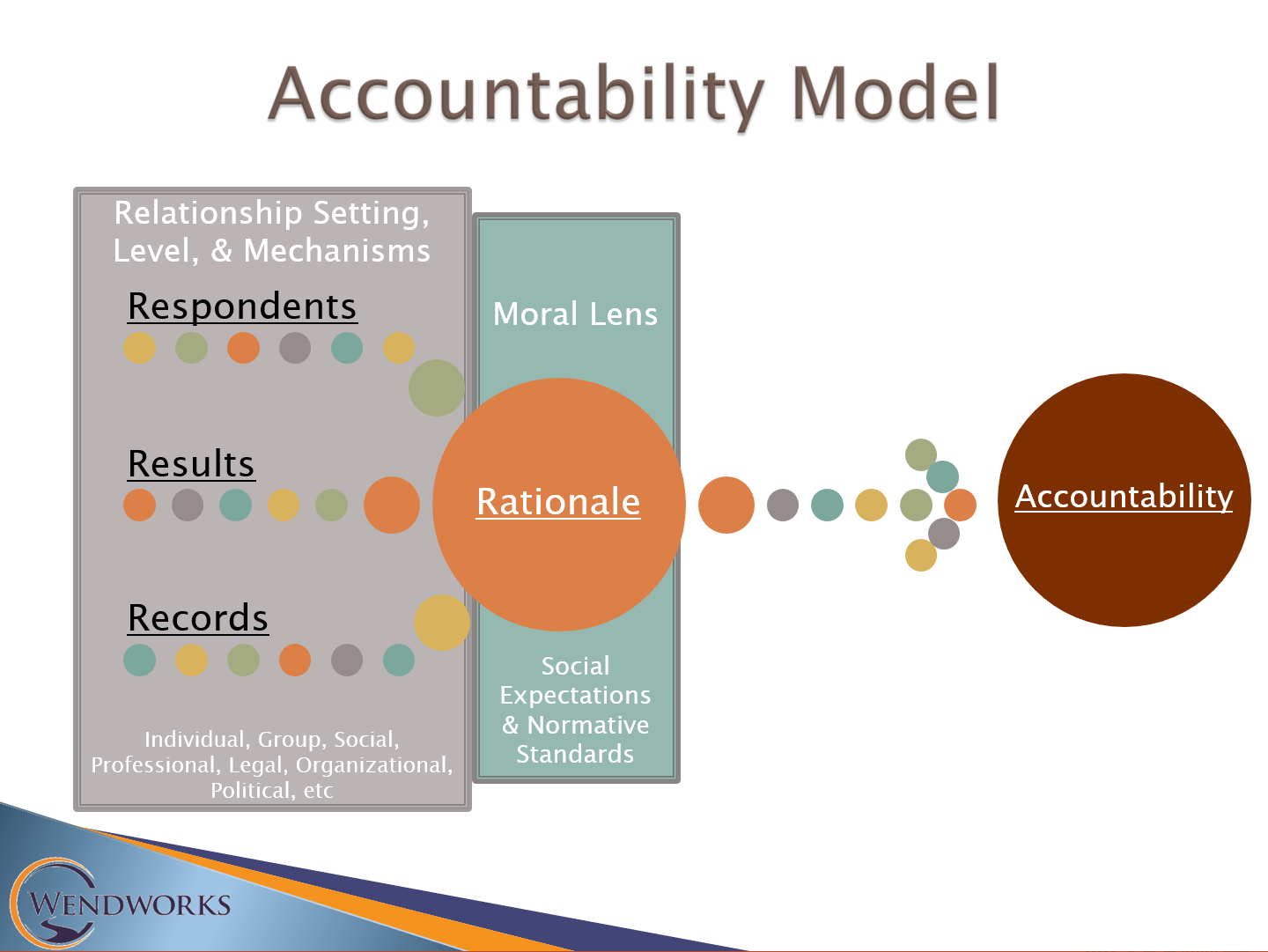

In a business meeting or social function, few words cut through the din and kill the mood more quickly than “accountability.” It is one of those words that instantly sets one on edge despite its familiarity and everyday usage. After the recent conviction of Derek Chauvin for the murder of George Floyd, policymakers and pundits alike pointed to accountability as they spoke about the trial outcome. Accountability is something that people understand, yet seems to become harder and harder to define the more one seeks to move beyond rhetorical flourishes to examine the word itself. For example, rather than providing a straightforward definition, Merriam-Webster’s listing for accountability leads one down a series of root-word associations such as accountable and account to ultimately land on something related to the four R’s of accountability: Respondents, results, records, and rationale.

Respondents: the decision-makers involved who either choose to accept or are compelled to respond to credit or blame assigned to them

Results: the events, activities, and outcomes for which someone may be held responsible

Records: the primary source data that details the transactions, decisions, or series of events leading to a given outcome

Rationale: the narrative arc that ties everything together to explain the conduct or decision-making of stakeholders related to the outcome and is understood through a moral lens of social expectations that community members hold about proper motives and correct behavior

Anyone can create a record by writing down events as they happen. However, for accountability to exist, stakeholders must be involved who have the ability to impact both the inputs and the outcomes for which they will be held accountable. Finally, an assumption or assignment of responsibility must be clarified and conferred on one or more people through the narrative laid out in the rationale. At its core, accountability is a story-telling exercise that uses data to assign credit for positive outcomes and blame for negative ones. It provides an “external view which simultaneously reflects, addresses, and confirms [one’s sense of] self” (Roberts, 1991, p. 357). Accountability is a simple word that belies its own complexity and depends largely on the subjective interpretations made and presented by the author of the rationale.

Stories have the power to shape organizational culture and serve to reinforce or destroy its capacity for meaningful accountability. George Orwell touched on this aspect of narrative power when he famously wrote in his book 1984 that “he who controls the past, controls the future: who controls the present controls the past.” In other words, organizational accountability is largely a function of current organizational culture, the agency of its people, and political power. Without a culture that systematically captures, understands, and evaluates the contribution of individuals toward specific outcomes, there is no meaningful way to assign credit or blame for results.

When employees are stripped of their agency, put to work with little or no autonomy, and denied opportunities to make meaningful decisions, they are no longer the heroes of their story or in control of the process. This diminishes the extent to which they may be meaningfully held accountable for outcomes as they have little to no power or agency to impact them. Power is a critical factor that impacts the way in which organizational narratives are framed and reflects the organizational level at which choice and control reside.

Accountability is hard for business leaders and researchers alike. In a paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association (2004), Dubnick and Justice speak to the difference between accountability as a commonly used word and “accountability-the-concept.” They show accountability as a commonly invoked concept that is messy, complex, and hard to measure in practice. And yet, “[m]ore than any other contemporary prescription, accountability has been offered as a solution for ills ranging from past injustices and corrupt behavior to unresponsive and incompetent… programs. These ‘promises’ of accountability” including justice, ethics, and performance “are so widely accepted that few have questioned the assumption about the capacity of the accountability cure to deliver on those promises” (Dubnick and Justic, p. 3).

With over 143,000,000 Google results for accountability and performance, management literature is replete with advice urging organizational leaders to use accountability as a tool to boost performance. Measuring performance is generally a straightforward proposition based on counting and tracking key performance indicators such as manufacturing outputs, gross sales, or net revenue. On the other hand, accountability is more difficult to measure directly. But without measurement, it cannot be evaluated and it is impossible for leaders to know whether accountability is increasing or decreasing over time. Without a way to measure it, accountability cannot serve as an effective leading indicator or tool to boost performance. So, how does one measure something as conceptually slippery as accountability?

Perhaps the most important step in measuring accountability is to distinguish between accountability the word, with many different shades of meaning and synonymic qualities, and accountability as a concept or framework to be operationalized and measured. As a human construct that exists only when two or more individuals come together, accountability is complex and cannot be reduced to a single data point. However, we can readily examine its constituent elements “as long as they are explicitly recognized as measuring only select components of a larger” accountability construct (Dubnick and Justice, p. 18). A theoretical framework serves this purpose well by providing a mechanism through which to understand the elements of accountability, break them apart, understand them, and tie them back together in ways that are empirically valid and ultimately useful.

Regardless of organizational size, leaders are seldom blessed with excess time and resources. They must prioritize the use of their time and attention where it will give them the best return on effort. Brandsma & Schillemans’ accountability cube provides a useful heuristic tool for organizational leaders seeking to understand, track, and prioritize their accountability efforts. The tool allows leaders to categorize issues and relationships along three dimensions so that they can focus on those of high consequence, where not enough information is known, and more discussion is needed. While a valuable tool for prioritization, it does little to unpack the process of accountability itself. For that, another model is needed.

The Accountability Cube

Accountability is the process by which people come together and make sense out of what happened or articulate their beliefs and expectations about what they believe the future should hold. It is the process that people, organizations, and societies use to determine where to give credit for positive outcomes and where to assign blame for accidents and failures. It requires clarity about what did or should happen, who was or will be involved, how results were or should be obtained, and whether results are positive or negative. It also requires a subjective assessment or evaluation of the actions and decisions leading up to an outcome that determines whether respondents acted morally, legally, or ethically, by displaying behavior that is in line with social and normative standards embraced by the community, organization, or society seeking to determine prospective or retroactive accountability.

So, what does this mean for leaders seeking to build a culture of accountability and performance? It means that the ability to hold people accountable is directly tied to the accountability levers below in which employees:

understand and agree with the organization on the outcomes for which they will be held accountable

know their role in the process and understand their contribution in ways that are clear, measurable, valued, and reliably recorded

trust the culture of the organization with respect to whether causal narratives are constructed and used with transparency, impartiality, and without corruption from power dynamics

reach consensus with others in the organization:

about what constitutes positive or negative outcomes within the organization

regarding normative standards and appropriate means of achievement

high levels of confidence that accountability for outcomes is regularly assigned to those whose choices and span of control ultimately determine the final outcome

These levers are simple to understand in concept but can be difficult in practice and to sustain over time. Thankfully, there are multiple ways to measure these levers within your organization that are relatively straightforward. Assessments and interventions will vary from organization to organization but regular monitoring and evaluation will show progress. More importantly, it can let you know when you get off track before a crisis occurs. Informed guidance can help, but it’s up to you to put in the effort.

Let’s get to work!

About the Author

David Macauley

A passionate business educator and innovator, David Macauley helps businesses and organizations succeed by developing, equipping, and empowering their people.

As a Convene's first Chair in Austin Texas, David engages business owners and CEOs to inspire business performance with an eternal perspective. David's Convene group members work in fellowship to profitably grow their businesses, build their leadership skills, and develop their people through peer-to-peer collaboration and one-to-one coaching. Click here to learn more and connect with David!

Bovens (2007). Analysing and Assessing Accountability: A Conceptual Framework. European Law Journal.

Newman (2020). He Who Controls the Narrative Controls the People. Medium.com

Roberts (1991). The possibilities of accountability. Accounting, Organizations and Society.

This article is used with permission and first appeared on the Wendworks company blog.